[ad_1]

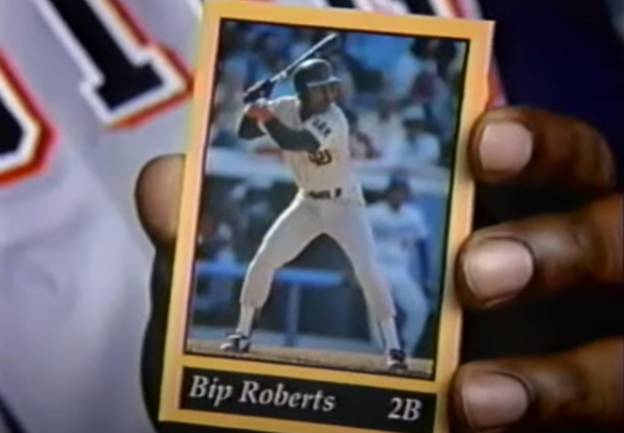

The 12 months is 1995. San Diego teammates Bip Roberts and Tony Gwynn, seated in an empty dugout, reflecting on a hard-fought labor battle or maybe the loving contact of an Arizona spring afternoon breeze, are speaking about baseball playing cards. Specifically, Roberts’ personal 1986 rookie card, which he declares to be value $275. “Twenty years from now,” he confides, “Who is aware of? One thousand, two thousand…”

Gwynn, idly thumbing via a worth information, corrects him, noting that it’s truly value 4 cents. In wonderful situation, Roberts retorts; ten cents in mint.

Roberts isn’t a lot of an funding adviser, because it seems. That ten-cent card, via the magic of inflation, would want to double in worth simply to maintain up with the price of residing. In actual life… effectively, it hasn’t. Mockingly, the baseball card bubble had already burst by the point the business aired, due to the mixed forces of the lockout and the trade’s mutually assured destruction via huge overproduction. Roberts’ true rookie card (technically 1987, not 1986; Bip did have a trio of 1986 playing cards, however they had been out there solely via interest shops, not customary units, so didn’t rely on the time) got here in what would later be described because the “junk wax period,” as producers cranked out cardboard at unfathomable charges. It’s not value 20 cents.

[ad_2]

Source link